Anolis roquet. Photo by Gaëll.

Read all about it in the latest issue of IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians.

Anolis roquet. Photo by Gaëll.

Read all about it in the latest issue of IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians.

Photo by Alan Franck, iNaturalist

Hey!

Since we had some questions about tail curling in Brown Anoles last week, I figured we should just talk about them today!

Anolis sagrei, or the Brown Anole or Bahaman Anole, is a trunk-ground anole whose range originally included islands like the Bahamas, Cuba, and the Cayman Islands. Brown Anoles are great stowaways and have now made it to the mainland US, other Caribbean islands and Pacific islands like Hawaii.

Brown Anoles can get up to 8.5 inches long (including their tail), and have a snout-to-vent length of about 55-60mm. They are, as their name suggests, often brown, but may also be grey. Despite the drab colouring, these anoles have a lot of variation in their patterns between individuals, with some almost looking plain and others appearing very striking with an array of spots, striping and marbling. Brown anole’s dewlaps are typically red-orange with a yellow border, but there are some who have splotches of yellow.

Since the introduction of another brown coloured anole, Anolis cristatellus (the Crested Anole), the two may be confused, but Brown anoles can be differentiated from them by the dewlap colouring (Crested anoles have opposite dewlap colours, typically yellow with a usually large border of orange), and if you can get close enough, by the presence or absence of light coloured ring around the eye or front limb stripe. Brown anoles don’t have this ring, but instead have dark eye bars (I like to think of it as winged eyeliner, that’s just how it registers the fastest in my mind). They also don’t have a light stripe above their front limb. Female Crested anoles have only a cream-coloured stripe down their backs that Brown anole females might have between diamond or bar patterning.

As we all may know ,they’re also very feisty anoles, going after questionable prey and prey larger than themselves. They are also one of several anoles that eat other anoles (and other lizards)!

Photo by Gecko Girl Chloe, iNaturalist

In the pet trade, Brown anoles with red/orange colouring are called Flame morphs, and lucky for you here’s a study on why that red might be showing up.

Photo by Sam Kieschnick, iNaturalist

I also get a lot of questions on Brown and Green anole interactions, typically about why Brown anoles are killing off Green anoles and here’s some posts to help answer that!

Flicker is the bimonthly publication of the Cayman Islands Department of the Environment. The October issue, available here, reports on the introduction of the green anole, Anolis carolinensis, to Grand Cayman, and on continuing efforts to remove green iguanas from that same island. Older issues are also available. If you’d like to receive future issues, contact the editor.

Aryeh Miller and Ansley Petherick

Thanks to all who submitted photos for the Anole Annals calendar contest–we received lots of great submissions! We’ve narrowed it down to the top 32, and now it’s time for you to vote! Here’s a slideshow of the finalists:

Choose your 6 favorites in the poll below. You can right-click on the thumbnail to view full-size images in the poll, check the box next to your picks. You have 13 days to vote – poll closes on 12/13/20 (a Sunday) at 11:59pm. Spread the word!

Periodically, we here at Anole Annals get reports of mating between green and brown anoles. Usually, it turns out to be a case of misidentification–often the “brown” anole is really a green anole in brown color phase, but sometimes it actually does happen. The most recent report comes from reader Rachel Easton, who tells the story of the picture above: “I’ve had them for a few weeks but they lived together at the pet store for months before I had them. They are in a 20 gallon in my greenhouse. This is the first time I’ve witnessed the mating behavior. I moved their tank to another location and about 3 minutes later they were mating. I occasionally see them displaying their throats at one another but I assumed it was a territorial dispute over the best basking spot.”

Photo by Steven Kurniawidjaja, iNaturalist

Hello! Hope you had a good Thursday!

I moved #DidYouAnole and shortened it for this week because of the holiday. We aren’t talking about one specific anole (or lizard) today, but just ideas on an observed behaviour.

Recently someone posted a picture of curly-tailed Brown Anole (Anolis sagrei) noting that they had been seeing this recently with the brown anoles in their area.

This intensity of tail curling, while typical of curly-tailed lizards (they’re named for it!), isn’t all too uncommon in anoles. For curly-tailed lizards, their tail curl is possibly used as part of anti-predator behaviour, meaning it helps them distract a predator away from their bodies, or makes them look bigger. Anoles also use their tails in a similar way, waving them during aggressive displays against other males and predators.

Photo by Bill Lucas, iNaturalist

Lizards use their tail in various kinds of signaling and tail curling is one that we have been observing but don’t quite know a lot about yet! Has anyone else observed this or have any ideas about tail curling behaviour?

Ecogeographical rules attempt to simplify ecological and evolutionary processes that shape morphology. In a cool study published this summer in Current Zoology, Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván (2020) examine the combined effect of Rensch’s Rule and van Valen’s Island Rule in Clouded Anoles. Specifically:

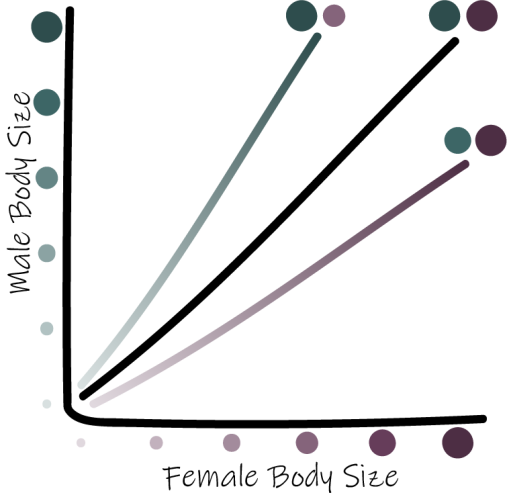

Rensch’s Rule: within lineages, sexual dimorphism decreases in magnitude with increased body size when females are the larger sex but increases in magnitude when males are the larger sex.

The center black line indicates 1:1 male to female size, the top line and bottom lines indicate male- and female-biased size dimorphism, respectively. *Adapted from Piross et al. 2019.

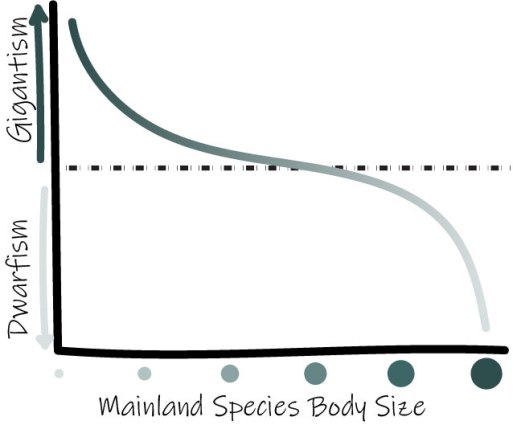

van Valen’s Island Rule: describes the tendency of diminutive and large mainland species to trend toward gigantism or dwarfism on islands, respectively, due to competitive factors.

*Adapted from Lomolino, 2005

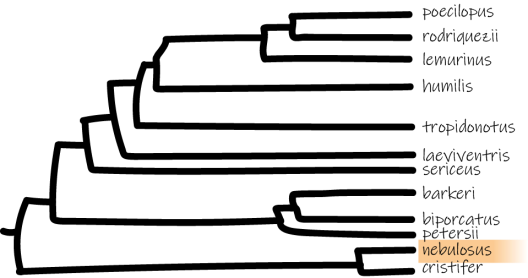

In their paper, Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván ask, how does Clouded Anole (Anolis nebulosus) sexual size dimorphism change when the Island Rule could be in effect?

Using 305 Clouded Anole museum specimens, they found that sexual size dimorphism differs between the mainland and island populations. While all populations revealed variation in the degree of sexual size dimorphism, populations on the Islas Tres Marías uniformly possess male-body size bias. But on the mainland, 40% of the populations had the opposite pattern, female-body size bias.

Intriguingly, Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván note that in the Clouded Anole, island males spend almost 50% more of their waking period engaged in some form of social interaction (Siliceo-Cantero et al. 2016). This is offered as an explanation for why male Clouded Anoles also have larger dewlaps among the Tres Marías populations.

In lizards, the Island Rule may not necessarily stand out as a trend (Meiri, 2007), but we see from Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván’s study that male Clouded Anoles are larger on islands. On the Antillean Islands, the magnitude of sexual size and shape dimorphism of anoles decreases with increased anole species diversity (Butler et al., 2007). The Islas Tres Marías populations follow this pattern in having increased sexual size dimorphism when not competing with other anole species.

*Adapted from Poe et al. 2017.

Overall, Clouded Anole body and dewlap sizes are larger in insular populations while Rensch’s Rule does not show a clean pattern in this species. However, as noted by the authors, it is important to consider the adaptive force of being on an island versus the ancestral condition. To truly understand morphological evolution within a species and across the genus we need to know body size trends of closely related species. Moreover, some researchers are discouraging studies that determine the universality of ecogeographical rules in favor of integrative approaches based around hypothesis testing (Lomolino et al. 2006, Lokatis & Jeschke, 2018).

What do you think? Is there room for using ecogeographical rules within an integrative framework (See Benítez-López et al. 2020)? Or do ecogeographical rules obscure true drivers of adaptation?

References:

Anaya-Meraz, Z. A., and A. H. Escobedo-Galván. 2020. Insular effect on sexual size dimorphism in the Clouded Anole Anolis nebulosus: when Rensch meets Van Valen. Current Zoology, doi: 10.1093/cz/zoaa034.

Benítez-López, A., L. Santini, J. Gallego-Zamorano, B. Milá, P. Walkden, M. A. J. Huijbregts, and J. A. Tobias. 2020. The island rule explains consistent patterns of body size evolution across terrestrial vertebrates. bioRxiv 2020.05.25.114835. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Butler, M. A., S. A. Sawyer, and J. B. Losos. 2007. Sexual dimorphism and adaptive radiation in Anolis lizards. Nature 447:202–205. Nature Publishing Group.

Lokatis, S., and J. M. Jeschke. 2018. The island rule: an assessment of biases and research trends. Journal of Biogeography 45:289–303. Wiley Online Library.

Lomolino, M. V. 2005. Body size evolution in insular vertebrates: generality of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography 32:1683–1699.

Lomolino, M. V., D. F. Sax, B. R. Riddle, and J. H. Brown. 2006. The island rule and a research agenda for studying ecogeographical patterns. Journal of Biogeography 33:1503–1510.

Meiri, S. 2007. Size evolution in island lizards. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16:702-708.

Piross, I. S., A. Harnos, and L. Rózsa. 2019. Rensch’s rule in avian lice: contradictory allometric trends for sexual size dimorphism. Scientific Reports 9:7908. Nature Publishing Group.

Siliceo-Cantero, H. H., A. García, R. G. Reynolds, G. Pacheco, and B. C, Lister. 2016). Dimorphism and divergence in island and mainland Anoles. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 118:852–872.

This post was originally published on biomh.wordpress.com.

Photo by Osoandino, iNaturalist

This week’s anole is one of three recorded species of anoles with a proboscis, the Pinocchio Anole, or Ecuadorian Horned Anole. The other two proboscid species being Anolis phyllorhinus and Anolis laevis.

Anolis proboscis has been featured on this website several times and is well loved here, so you may already know that only the males have the proboscis.

They are capable of raising and lowering their appendages and use it for attracting mates. They move their heads side to side in displays referred to as ‘proboscis flourishing’ (Quirola et al. 2017). Males also stimulate females during courtship, by rubbing the nape of their necks with the appendage. The horn can’t be used as a weapon for fighting other males as it is very flexible, capable of folding right over (Losos et al. 2012), but they display their horns during these interactions, raising them, most likely to appear larger and more intimidating to the rival male. Their dewlaps are small, which is common in anoles with other physical signals, but more research is needed into the uses of the appendage to further confirm its uses.

Female Pinocchio Anole, photo by Nelson Apolo, iNaturalist

The Pinocchio Anole males, unlike other proboscid anoles, are born with a small horn. Why do they have the horn so early? We don’t know… yet!

This anole is very hard to find, actually even being assumed extinct after going unseen by locals and visiting scientists alike, after specimens were collected in 1966, until accidentally being spotted by a birdwatching group in 2005 when a male crossed the road. They typically prefer dense vegetation but on occasion may be found active on the ground. Pinocchio Anoles are endangered, and only found in the protected forest reserves that make up their range in Ecuador, where they are endemic.

In the (sub)tropics of the Western Hemisphere, it is not uncommon to come across sleeping anoles while strolling around at night in (partially) vegetated areas; they are after all considered diurnal. It was therefore quite a shock when active anoles appeared in the beam of our headlights during the nights of 18 January and 16 April 2019 on the Commonwealth of Dominica. On the first night, we observed how a juvenile Anolis cristatellus (non-native) jumped from one grass style to the next and successfully caught a fly; on the second night, the adult A. cristatellus had a still alive and resisting, frog (Eleutherodactylus martinicensis) in its mouth (see photo).

An increasing number of anole species are being found to utilize artificial light sources after sunset, and thereby extend their activity period, allowing increased growth and fecundity. What made our encounter especially unsuspected was the absence of artificial light in the area we were surveying for the removal of newly arrived alien species. Instead, these nights (waxing gibbous with 91.7-92.9% visibility) were close to the full moon, and without cloud cover. Our observations were at 19:59 and 20:40h, almost 2 hours after the end of astronomical twilight; it was night.

The area of our observations consists of several abandoned plots nearby the harbor, overgrown with grasses, vines, and bushes. The edges of this open area are partially made up of a single line of trees, shorter than 7 m in height.

Our observations indicate a potential understudied part of anole ecology, though more observations are needed to understand the occurrence of this behavior, both within and among species. However, ex-situ, some authors have already demonstrated that anoles show activity under moonlight conditions, which appeared more evident for shade-adapted species.

In our paper just published in Neotropical Biodiversity, we discuss several to-be-tested hypotheses and address how our observations could shed new light on anole predation by nocturnal predators, like owls and bats. Beyond anoles, observations of nocturnal activity by diurnal reptiles have been reported on some occasions. The observations of this behavior in Anolis are of special importance given the large body of literature and understanding of these model species; allowing the scientific community to test hypotheses and move beyond observational reports.

Excitingly, since the publication of our work we have been in contact with enthusiast readers of which one indicated to have observed moonlight-facilitated activity as well but did not write that up, yet.

Matt R. Whiles, Chair and Professor in the Soil and Water Sciences Department at the University of Florida provides these details:

Specimen was not captured, just photographed by my wife Lindsay Hsieh, who is familiar with Anolis and recognized that it was different looking. Observed in Alachua county FL, west of Gainesville in a horse barn facility – coordinates: 29O 41’08”N 82O 30’18”W; date was November 10 2020. A. carolinensis are common on the barn, but none we’ve seen look like this. The owners of the facility routinely haul horses back and forth from Gainesville to south Florida, so could be a transplant.”

He then asks: “I’ve seen thousands of A. carolinensis, and never one like this. Do you think this is just a color/pattern display, or would this individual always look like this? We are keeping an eye out for it again and will try to collect it if you want the specimen.”

Thoughts, anyone (including interest in the specimen should it be seen again)? My guess is that these are not permanent markings; the block spot on the head and the hint of an erected nuchal (neck) crest suggests a stress response; perhaps the lizard had just been fighting. Indeed, Dr. Whiles clarified in a subsequent email: “I’ve certainly seen the black spot form on stressed individuals, but never the full patterning. To add to your hypothesis, my wife indicated it was interacting with another Anolis when she saw it (you can actually see the tail of the other individual in the pic).”

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén