Female brown anole (Anolis sagrei).

My foray into lizard studies (including anoles) began when I joined Bob Cox’s (no relation!) laboratory at the University of Virginia around three years ago, after years of studying the evolution and physiology of snakes (e.g., Cox and Secor 2008; Cox and Secor 2010; Cox et al. 2012; Cox and Davis Rabosky 2013). One aspect of anoles that fascinates me is that they exhibit great diversity in sexual dimorphism (any difference in any trait between the sexes). Many species are highly dimorphic in traits like head shape, dewlap size (and color), and body size, while other species are sexually monomorphic in some or all of these traits. This evolutionary diversity in whether or not a trait differs between the sexes suggests that dimorphism can evolve relatively rapidly. These traits are likely encoded by genes on the shared autosomal genome and thus shared between the sexes, which should theoretically impede evolution of these traits. One solution to this problem is to link the expression of shared traits (such as dewlaps, head shape, and body) to sex steroids (androgens and estrogens). However, typically “female” steroids such as estrogens have important functions in males (e.g., Sanger et al. 2014), and typically “male” steroids such as testosterone have important functions in females (e.g., Ketterson et al. 2005). Thus, the evolution of sexual dimorphism requires not only linking the expression of dimorphic traits to testosterone in males, but also unlinking testosterone from the expression of these traits in females. Unfortunately, reflecting the recent post by Ambika Kamath pointing out the paucity of research on female anoles, we know relatively little about how testosterone impacts growth and development in female lizards. Our work begins to address this issue by studying how both male and female brown anoles respond to testosterone (Cox et al. 2015).

Male (left) and female (right) brown anoles. The males are much larger, with bigger dewlaps. Males and females differ in body shape and coloration as well.

Our research was focused on brown anole lizards (Anolis sagrei), which have become commonly used in evolution and ecology research. This species was ideal for our studies because they are very sexually dimorphic, with males much larger than females (averaging up to 33% longer, and three times as massive), possessing much larger dewlaps, along with a suite of other morphological divergences (differently shaped heads, longer forelimbs, etc). Importantly, previous work by Bob Cox and Ryan Calsbeek (and their collaborators) has shown that the expression of many of these traits is altered by testosterone, which naturally circulates at much higher levels in males (Cox et al. 2009a; Cox et al. 2009b). We followed up that previous research and used hormone manipulations to test how testosterone impacts the development of a suite of sexually dimorphic characters in both males and females. We were specifically interested in testing whether females could respond to testosterone and whether or not they responded to testosterone in the same way as males. If females respond to testosterone as males do, then this implies that the decoupling of dimorphic trait expression between the sexes is accomplished merely by circulating testosterone at lower levels in females.

X-ray of juvenile brown anoles

We conducted this experiment on juveniles (offspring of brown anoles captured from Great Exuma in The Bahamas) that were 5-6 months of age at the beginning of the experiment. This is a point in development when sexual dimorphism is just starting to develop, but the sexes are still pretty similar. We used small Silastic implants (about 5 mm in length) that were filled with either crystalline testosterone or a control. These implants were then surgically implanted into the coelomic cavity of both male and female anoles. Most of my limited surgery experience has been with snakes (mostly Burmese pythons as part of my Master’s work with Stephen M. Secor at the University of Alabama), so it was interesting to learn the techniques used for small (about 2 g) lizards. We simply opened a small abdominal incision, inserted the implant, and the closed the opening with skin glue. We then allowed the lizards to develop naturally in the brown anole colony at the University of Virginia for about two months. At the end of that period, we measured a suite of traits in both sexes, including size (mass and length), metabolic rate, fat storage (by weighing the visceral fat bodies), growth of various skeletal elements (via X-rays), and dewlap size and color.

The dewlap was extended and traced on graph paper to measure area.

We found that males and females brown anoles responded similarly to testosterone for most traits. Both sexes with testosterone grew faster than the control animals, and females given testosterone grew at similar rates to males with testosterone. Testosterone also increased metabolic rate, and a decreased the amount of fat stored in both sexes. Beyond growth and energetics, we also found that testosterone stimulated the size and darkened the color (decreased brightness and saturation) of the dewlap. Interestingly, we did not find an impact of testosterone treatment on head shape (jaw length and head width) in either sex, which is perhaps not surprising in the light of Thom Sanger’s (and colleagues) work highlighting the role of estrogens in skull development (Sanger et al. 2014).

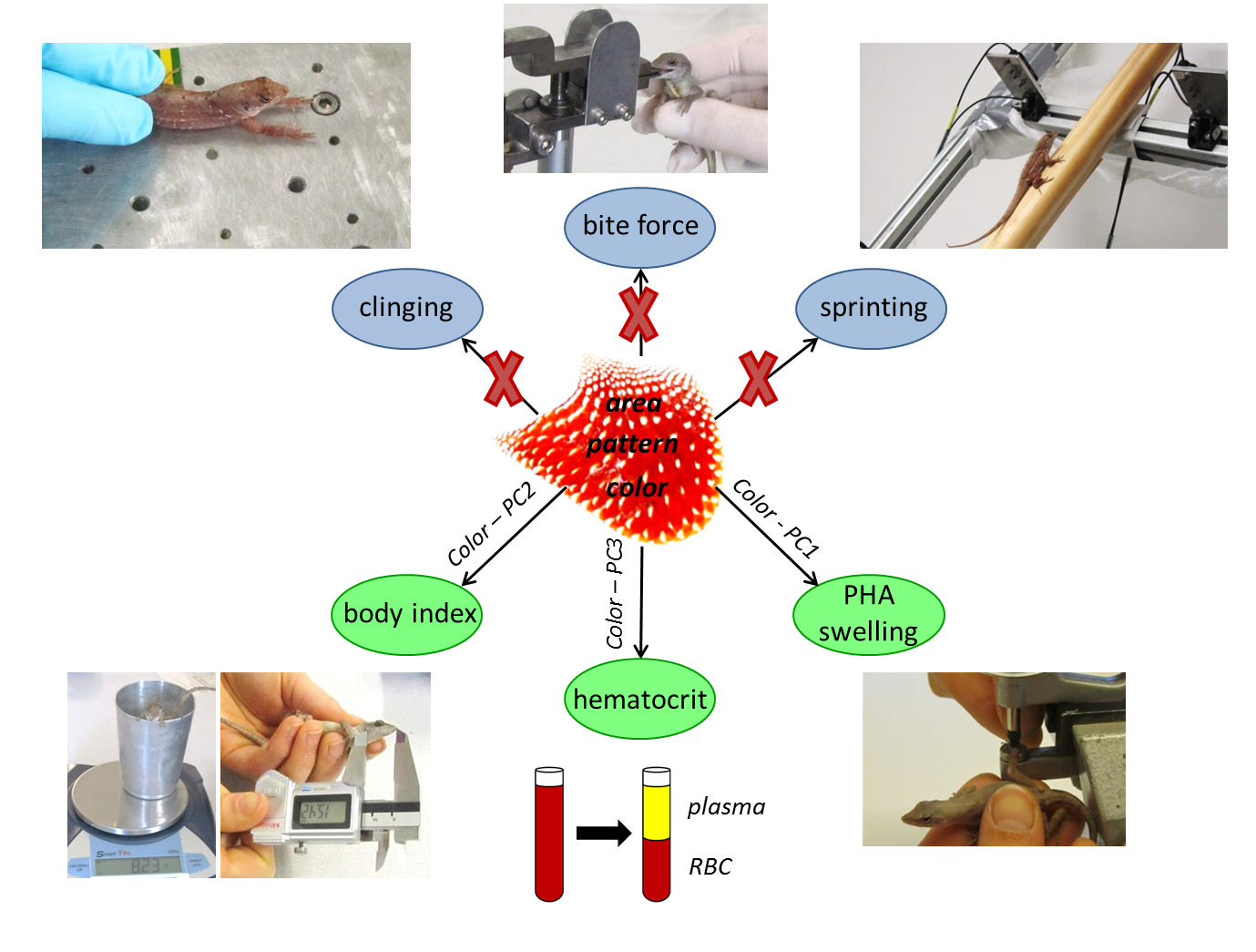

Summary figure of the primary results from our recent paper (Cox et al 2015) on the impact of testosterone on the development of various traits.

Our work demonstrates that despite differing greatly in appearance from males, female brown anoles retain the physiological capacity to respond to T similarly to males, at least as juveniles. Thus, the evolution of sexual dimorphism in brown anoles can be explained simply by higher circulating testosterone in males. More broadly, our work suggests that sexual dimorphism can evolve simply by coupling trait expression to differences between the sexes in circulating testosterone, without unlinking trait expression from testosterone in females. Some of our recent and ongoing work continues to explore these themes by examining how testosterone impacts tissue-level transcriptomes and gene expression of growth-regulatory networks in brown anoles of both sexes, and how the gene expression response to testosterone might differ between species with different patterns of sexual dimorphism. Our ultimate goal with this research is to understand how the evolutionary modulation of interactions between developmental networks mediates the evolution of sexual dimorphism.

References

Cox, C. L., and A. R. Davis Rabosky. 2013. Spatial and temporal drivers of phenotypic diversity in polymorphic snakes. American Naturalist 182:E40-E57.

Cox, C. L., A. F. Hanninen, A. M. Reedy, and R. M. Cox. 2015. Females retain responsiveness to testosterone despite the evolution of androgen-mediated sexual dimorphism. Functional Ecology 29:758-767.

Cox, C. L., A. R. D. Rabosky, J. Reyes-Velasco, P. Ponce-Campos, E. N. Smith, O. Flores-Villela, and J. A. Campbell. 2012. Molecular systematics of the genus Sonora (Squamata: Colubridae) in central and western Mexico. Systematics and Biodiversity 10:93-108.

Cox, C. L., and S. M. Secor. 2008. Matched regulation of gastrointestinal performance in the Burmese python, Python molurus. Journal of Experimental Biology 211:1131-1140.

—. 2010. Integrated postprandial responses of the diamondback water snake, Nerodia rhombifer. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 83:618-631.

Cox, R. M., D. S. Stenquist, and R. Calsbeek. 2009a. Testosterone, growth and the evolution of sexual size dimorphism. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 22:1585-1598.

Cox, R. M., D. S. Stenquist, J. P. Henningsen, and R. Calsbeek. 2009b. Manipulating testosterone to assess links between behavior, morphology, and performance in the brown anole Anolis sagrei. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 82:686-698.

Ketterson, E. D., V. Nolan Jr., and M. Sandell. 2005. Testosterone in females: mediator of adaptive traits, constraint on sexual dimorphism, or both? The American Naturalist 166:S85-S98.

Sanger, T. J., S. M. Seav, M. Tokita, R. B. Langerhans, L. M. Ross, J. B. Losos, and A. Abzhanov. 2014. The oestrogen pathway underlies the evolution of exaggerated male cranial shapes in Anolis lizards. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 281:2014039, online early.