For decades, we anole scientists have been fascinated by the marvelous throat fans, called ‘dewlaps,’ characterizing Anolis lizards. A bunch of brilliant studies have therefore focused on the origin, evolution, diversity and function of this structure, revealing important pieces of what seems to be a complex ‘dewlap puzzle.’ And I think you all agree that the answer to what might look like a rather simple question at first, i.e., ‘what does the dewlap say,’ is not evident at all. So, with our study we aimed to add an ‘extra’ piece to the puzzle, which may help to further unravel the exact nature of information conveyed by the Anolis dewlap.

For decades, we anole scientists have been fascinated by the marvelous throat fans, called ‘dewlaps,’ characterizing Anolis lizards. A bunch of brilliant studies have therefore focused on the origin, evolution, diversity and function of this structure, revealing important pieces of what seems to be a complex ‘dewlap puzzle.’ And I think you all agree that the answer to what might look like a rather simple question at first, i.e., ‘what does the dewlap say,’ is not evident at all. So, with our study we aimed to add an ‘extra’ piece to the puzzle, which may help to further unravel the exact nature of information conveyed by the Anolis dewlap.

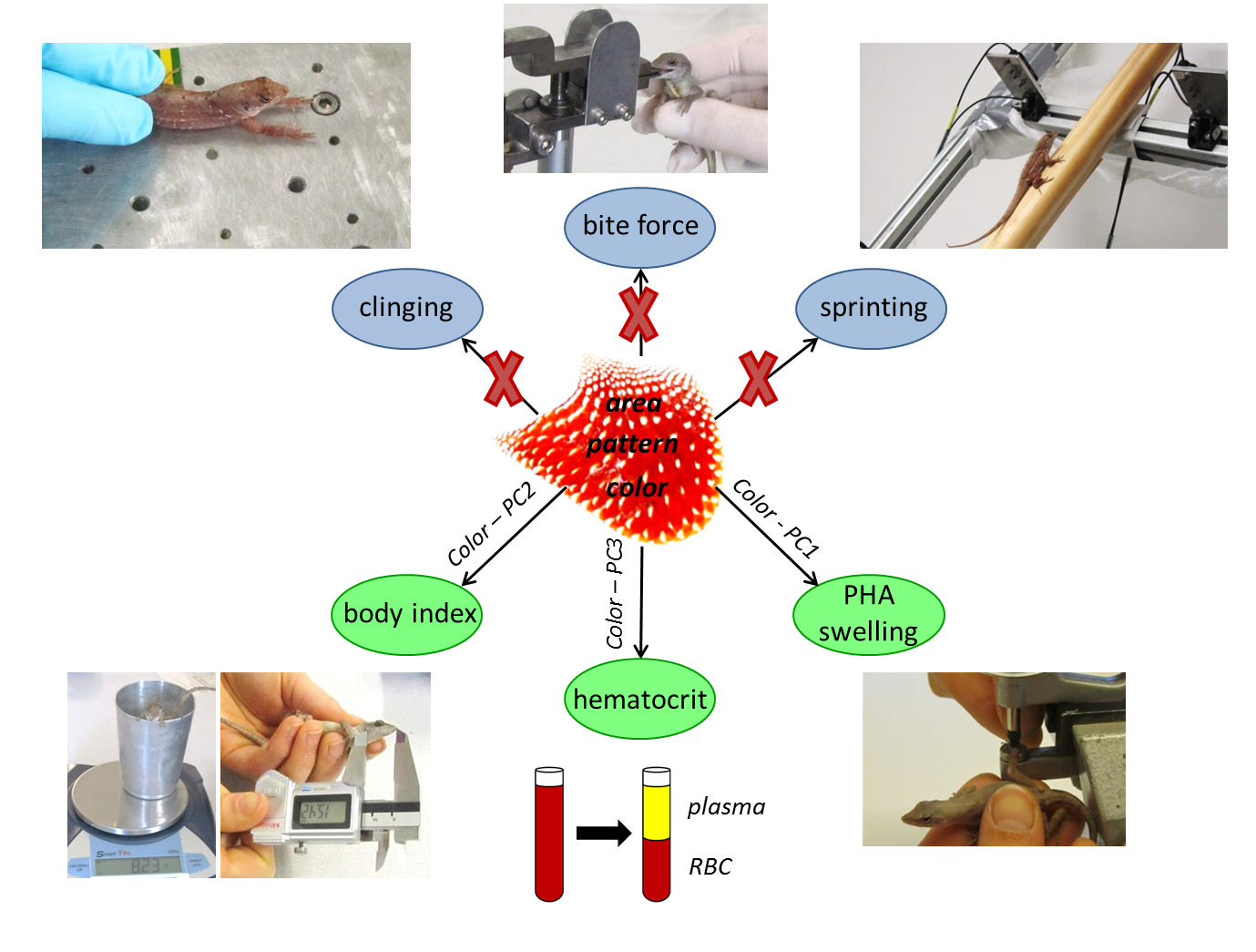

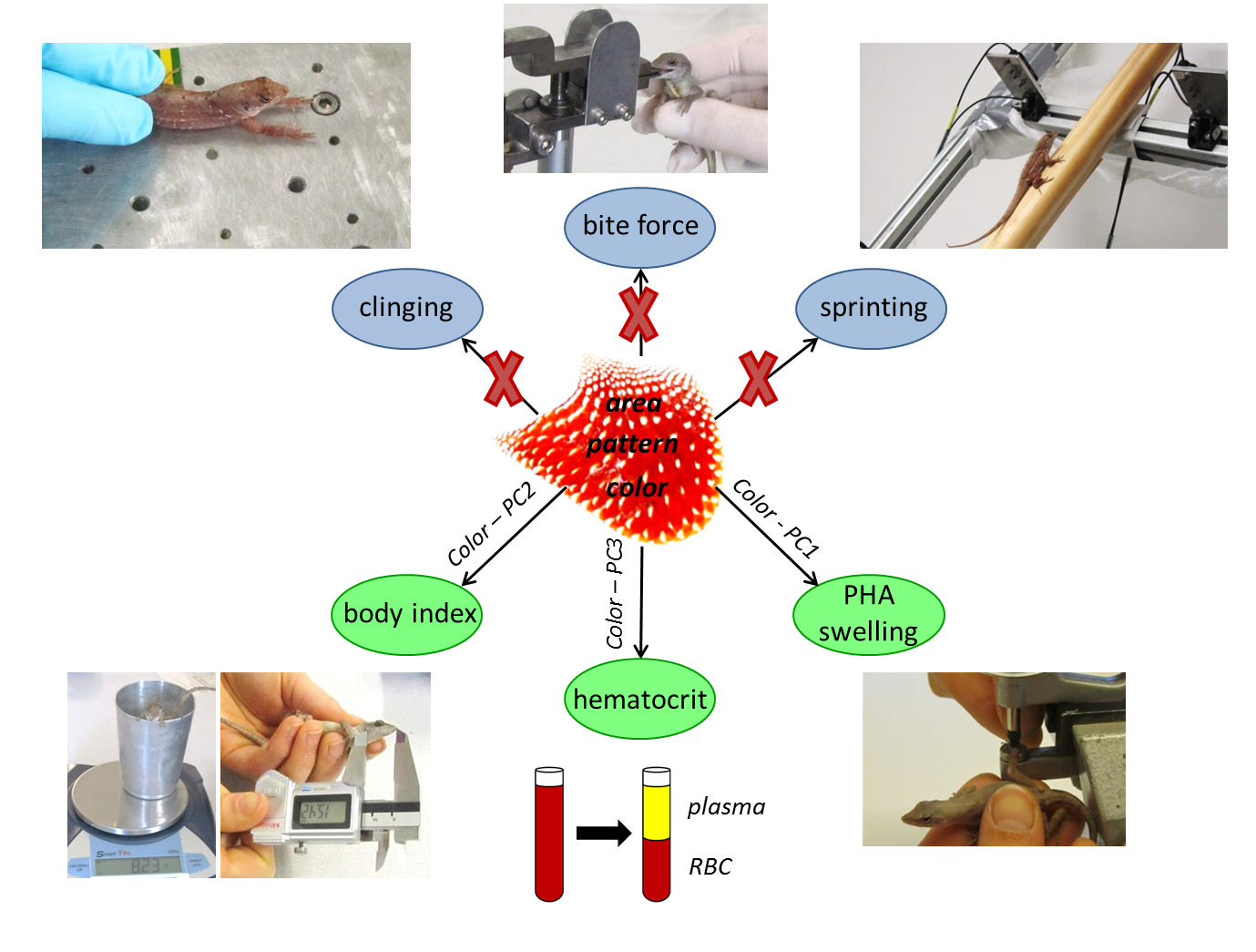

We specifically focused on what is signaled by various components of the dewlap in the brown anole and whether diverse aspects of dewlap signaling provide additive information or highlight different characteristics of the sender. We therefore measured several dewlap components involving design (i.e., dewlap area, patterning, and color) and use (i.e., dewlap extension frequency during intersexual interactions), and linked these to information a sender may need to transmit in order to increase its fitness (i.e., sexual identity, individual quality, and social status). We used several performance (i.e., bite force, sprint speed, and clinging capacity) and health state parameters (i.e., immunocompetence, hematocrit, and swelling response) as a measure of individual quality, whereas mirror-motivated aggressiveness was used as a measure of social status. Due to their fundamentally divergent reproductive roles, we expected males and females to differ with respect to what is signaled by the dewlap, and therefore performed separate analyses per sex. For the male sex, we additionally distinguished between the color of the dewlap center and edge region.

What did our results show?

First, we found that body size together with relative dewlap area and color act as redundant messages in the advertisement of sexual identity. Depending on the distance between signaler and receiver and prevailing environmental conditions, recognizing a potential mating partner based on the estimation of its body size only may be a hard task to fulfill. We therefore suggest that repeating the same message in different ways using body size together with dewlap traits is a highly appropriate strategy to get information about sexual identity accurately across.

Second, we found that dewlap coloration is primarily responsible for signaling aspects of individual quality, but only in males. Our results show that individual health state parameters are reflected in the color components of both male dewlap center and edge and that multiple different messages are conveyed by dewlap color. Specifically, we found that males bearing dewlaps with higher amounts of yellow and red and lower amounts of UV show higher body condition indexes, and that individuals with generally brighter dewlaps have lower immunocompetence. In addition, males with more yellow and UV chroma in dewlap edge only exhibit higher hematocrit values.

Surprisingly, none of the tested components of dewlap design in A. sagrei males conveyed information on performance capacities and aggressive behavior, and the same result was found for dewlap use. Also, no links were observed between components of dewlap design and use during intersexual interactions.

Third, for females, neither dewlap design nor use were related to any of the tested individual quality measurements and mirror-induced aggression. However, in contrast to males, correlations between components of dewlap design and use were found in A. sagrei females. Female individuals with larger dewlaps showed higher dewlap extension frequencies during intersexual interactions only and the same is true for individuals with less bright dewlap centers, suggesting an important signaling function of the female dewlap during courtship.

What can be concluded?

Our study confirms that the dewlap signaling device is a very complex integrated system consisting of different components transferring redundant (sexual identity) as well as non-redundant information (individual quality). We found that both the dewlap center and edge bear a signaling function, but this was only tested in males. As expected, male and female dewlaps differ in the messages they convey and further research is absolutely necessary to get insights in ‘what the dewlap exactly says’.

Driessens, T., Huyghe, K., Vanhooydonck, B. and Van Damme, R. (2015). Messages conveyed by assorted facets of the dewlap, in both sexes of Anolis sagrei. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. DOI 10.1007/s00265-015-1938-5