Above: the territorial display of a male Anolis stratulus on Puerto Rico

Take the time to watch the displays of an anole and you might appreciate how elaborate those signals seem to be. And by comparison to other lizard species, the anole display is arguably one of the most complex. Not only do anoles communicate with the up/down movement of head-bobs, but with the repeated extension of a large dewlap that in itself is often spectacularly colored. These displays are used to convey a variety of messages, from advertising the ownership of territories to the attraction of mates. We know the display is packed full of detail on species identity too.

But how do we go from gut impressions of what is complex to properly measuring the complexity of lizard displays, or any form of animal communication for that matter, including human language? The main way scientists have done this is by essentially counting the number of different components and using that to estimate an animal’s communication repertoire. There are various problems with this, such as deciding which components are different enough to count. It’s the most common method probably because it’s the easiest, but it is also the crudest. It offers only a basic view of signal complexity, missing the complexity inherent within components making up the repertoire.

An alternative approach is to apply some math from physics to measure the information potential of a signal. It is better than simply counting things because it measures the complexity of the entire signal, including the number of different components and the elaborations within those individual components as well. Best of all, it doesn’t require any decisions on what parts of a signal might be worth counting. It also provides a common, repeatable index of complexity that can be used to compare signals from very different animals, such as anole displays and human language.

So, how do anole displays stack up?

Want to know whether Anolis pulchellus on Puerto Rico has the most complex display? Read the paper and find out!

First, let’s consider some other lizards. The head-bob displays of sagebrush lizards (Sceloporus graciosus) are fairly representative of other species of fence lizards, and they clock in at 4.26 bits of information per display. “Bits” is a general unit for the amount of ‘information’ (think data) that can be “potentially” encoded in a signal, or its “information potential” for short. The number is largely meaningless by itself. The songs of birds would probably be the most obvious rivals of complexity in nature. Chickadees have 4.64 to 5.79 bits per song. But is that effectively the same or way more complex than sagebrush lizards? We need more benchmarking.

How about the famous waggle dance of the honeybee? The waggle dance was first uncovered by Karl von Frisch who found that it was a highly accurate signal conveying the direction and distance to an outside nectar source to worker bees inside the hive (google it, it really is super interesting). This discovery later contributed to von Frisch winning the Nobel Price alongside Konrad Lorenz and Nikko Tinbergen. von Frisch was also one of the first scientists to apply information theory to animal communication. The honeybee waggle dance comes in at 7.43 bits per dance. Bees are more complex than birds!

If we apply the same method of measuring complexity to written English, we find it has about 8.12 bits per word. Now let’s recap: sagebrush lizards are 4.26 bits per headbob display, chickadees are 4.64-5.79 bits per song, the honeybee waggle dance (my personal favourite) is 7.43 bits per dance, and written English is about 8.12 bits per word. Those comparisons in themselves are very interesting, but what about anole displays?

We’ve comprehensively measured the male territorial displays of eight different species of Puerto Rican anole and published our findings in Behavioral Ecology. When I say comprehensive, I mean just that: we measured dewlap colour pattern, the way in which the dewlap is repeatedly extended and retracted during the display, the pattern of movement of both push-ups and head-bobs, and a variety of other behaviors often seen accompanying territorial displays (e.g., tail curls and flicks).

The least complex part of the display is the dewlap colour pattern. At best, it encodes 1.02 bits per dewlap pattern. That’s for a dewlap with at least four different colours. The movement of the dewlap during the display—the timing of the in/out movement, how much the dewlap is extended—has far more information potential with as much as 3.87 bits per display. The sequence of head-bobs is the most complex aspect of the anole display and can be as high as 5.11 bits per display. Considering the entire display, the complexity of the territorial display ranges from 6.54 bits per display in Anolis poncensis to a whopping 15.40 bits per display in Anolis pulchellus.

15.40 bits per display! Does this mean anole displays are more complex than written English? Yes! And no. The estimate for written English—8.12 bits per word—was for single words, not a sentence, a paragraph or an encyclopedia. But the fact that anole displays are as complex as they are and might outclass songbirds is truly amazing.

It is contentious as well. During peer-review of our paper, some scientific referees found the reported values hard to digest. All of them thought our numbers for anoles were correct, but couldn’t accept that signals of mere lizards might be more complex than those of songbirds. The comparison to written English drew so much heat that we had to remove comparison to it from the paper entirely. The referees had various reasonable points. One referee highlighted that the value for written English was for single words, not whole texts (fair enough). Another referee suggested our application of information theory was more comprehensive than how it has been previously applied. The implication being other studies have tended to focus on measuring the easiest things and not the full breadth of a song (hmm…).

If you want to find out which Puerto Rican anole species varied most in display complexity and the adaptive explanations of why, or what might have driven the evolution of such complex signals in anoles to begin with, you’ll have to read our paper. Email me and I’ll send you a free copy.

Anoles outclass songbirds? Why not, I say. Perhaps in communicative complexity, but certainly on many other scales.

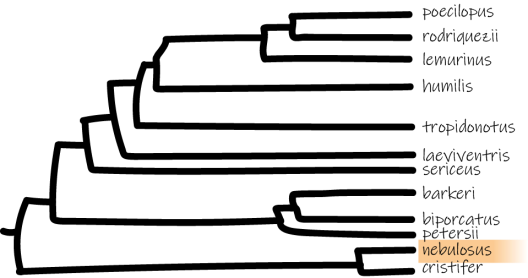

Ecological differences may accelerate the speciation process. Anolis cooki and Anolis cristatellus are two Puerto Rican species that are closely related but occupy very different habitats.[/caption]

Ecological differences may accelerate the speciation process. Anolis cooki and Anolis cristatellus are two Puerto Rican species that are closely related but occupy very different habitats.[/caption]