Ecogeographical rules attempt to simplify ecological and evolutionary processes that shape morphology. In a cool study published this summer in Current Zoology, Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván (2020) examine the combined effect of Rensch’s Rule and van Valen’s Island Rule in Clouded Anoles. Specifically:

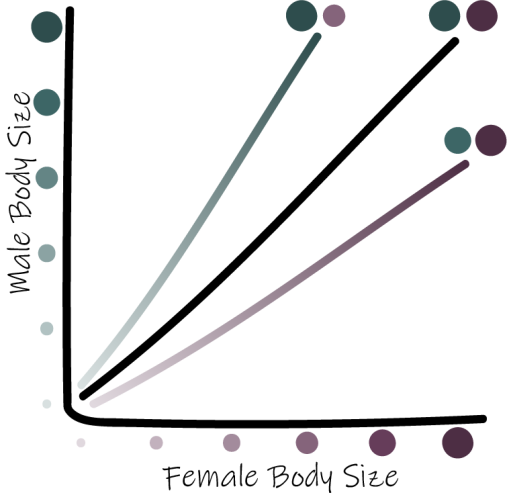

Rensch’s Rule: within lineages, sexual dimorphism decreases in magnitude with increased body size when females are the larger sex but increases in magnitude when males are the larger sex.

The center black line indicates 1:1 male to female size, the top line and bottom lines indicate male- and female-biased size dimorphism, respectively. *Adapted from Piross et al. 2019.

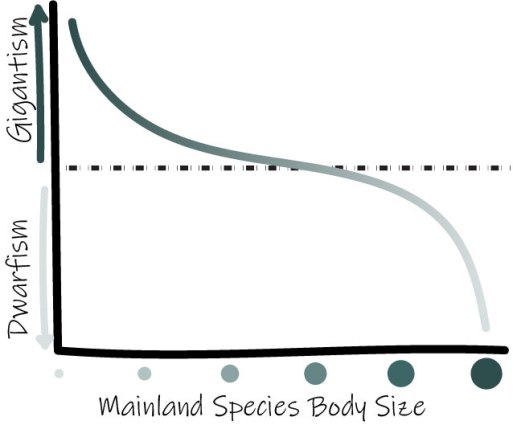

van Valen’s Island Rule: describes the tendency of diminutive and large mainland species to trend toward gigantism or dwarfism on islands, respectively, due to competitive factors.

*Adapted from Lomolino, 2005

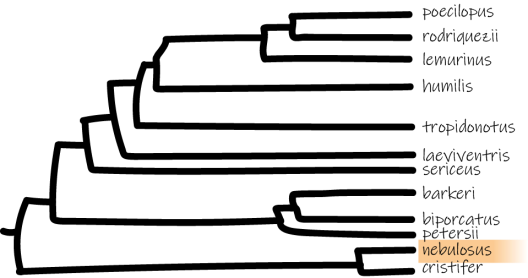

In their paper, Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván ask, how does Clouded Anole (Anolis nebulosus) sexual size dimorphism change when the Island Rule could be in effect?

Using 305 Clouded Anole museum specimens, they found that sexual size dimorphism differs between the mainland and island populations. While all populations revealed variation in the degree of sexual size dimorphism, populations on the Islas Tres Marías uniformly possess male-body size bias. But on the mainland, 40% of the populations had the opposite pattern, female-body size bias.

Intriguingly, Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván note that in the Clouded Anole, island males spend almost 50% more of their waking period engaged in some form of social interaction (Siliceo-Cantero et al. 2016). This is offered as an explanation for why male Clouded Anoles also have larger dewlaps among the Tres Marías populations.

In lizards, the Island Rule may not necessarily stand out as a trend (Meiri, 2007), but we see from Anaya-Meraz and Escobedo-Galván’s study that male Clouded Anoles are larger on islands. On the Antillean Islands, the magnitude of sexual size and shape dimorphism of anoles decreases with increased anole species diversity (Butler et al., 2007). The Islas Tres Marías populations follow this pattern in having increased sexual size dimorphism when not competing with other anole species.

*Adapted from Poe et al. 2017.

Overall, Clouded Anole body and dewlap sizes are larger in insular populations while Rensch’s Rule does not show a clean pattern in this species. However, as noted by the authors, it is important to consider the adaptive force of being on an island versus the ancestral condition. To truly understand morphological evolution within a species and across the genus we need to know body size trends of closely related species. Moreover, some researchers are discouraging studies that determine the universality of ecogeographical rules in favor of integrative approaches based around hypothesis testing (Lomolino et al. 2006, Lokatis & Jeschke, 2018).

What do you think? Is there room for using ecogeographical rules within an integrative framework (See Benítez-López et al. 2020)? Or do ecogeographical rules obscure true drivers of adaptation?

References:

Anaya-Meraz, Z. A., and A. H. Escobedo-Galván. 2020. Insular effect on sexual size dimorphism in the Clouded Anole Anolis nebulosus: when Rensch meets Van Valen. Current Zoology, doi: 10.1093/cz/zoaa034.

Benítez-López, A., L. Santini, J. Gallego-Zamorano, B. Milá, P. Walkden, M. A. J. Huijbregts, and J. A. Tobias. 2020. The island rule explains consistent patterns of body size evolution across terrestrial vertebrates. bioRxiv 2020.05.25.114835. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Butler, M. A., S. A. Sawyer, and J. B. Losos. 2007. Sexual dimorphism and adaptive radiation in Anolis lizards. Nature 447:202–205. Nature Publishing Group.

Lokatis, S., and J. M. Jeschke. 2018. The island rule: an assessment of biases and research trends. Journal of Biogeography 45:289–303. Wiley Online Library.

Lomolino, M. V. 2005. Body size evolution in insular vertebrates: generality of the island rule. Journal of Biogeography 32:1683–1699.

Lomolino, M. V., D. F. Sax, B. R. Riddle, and J. H. Brown. 2006. The island rule and a research agenda for studying ecogeographical patterns. Journal of Biogeography 33:1503–1510.

Meiri, S. 2007. Size evolution in island lizards. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16:702-708.

Piross, I. S., A. Harnos, and L. Rózsa. 2019. Rensch’s rule in avian lice: contradictory allometric trends for sexual size dimorphism. Scientific Reports 9:7908. Nature Publishing Group.

Siliceo-Cantero, H. H., A. García, R. G. Reynolds, G. Pacheco, and B. C, Lister. 2016). Dimorphism and divergence in island and mainland Anoles. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 118:852–872.

This post was originally published on biomh.wordpress.com.