Anolis fairchildi from Cay Sal Island, Bahamas. Photo by R. Graham Reynolds.

In a previous post, I introduced some results from our attempts to understand the evolutionary history of anoles on Cay Sal Bank, Bahamas (more results in a future post). We found that the only endemic reptile on the Bank, Anolis fairchildi (the Cay Sal Anole), is a lineage relatively recently derived from western Cuban A. porcatus progenitors. OK, fair enough, but what is this creature we list in our checklists and museum collections with the epithet fairchildi? A comment by James Stroud on a previous post of mine suggested that we visit this species directly here on AA, so off we go!

The anole specimens leading to the description were collected by Paul Bartsch in 1930, a malacologist who spent a week on the bank (Buden 1987). Bartsch found specimens on both Cotton Cay and Cay Sal (more on distribution below). In this manuscript (Barbour and Shreve 1935), Thomas Barbour offers a narrative of an Utowana expedition in 1934 during which time the explorers, including Barbour and J.C. Greenway–another name that lingers after several Latin generic names (e.g. Leiocephalus greenwayi)–sought herpetological novelties. It is worth noting that Barbour and his team secured a “rich booty” of land mollusks (Barbour and Shreve 1935); in other words, they weren’t always just after reptiles and were likely offering tit-for-tat with Paul Bartsh (my opinion). This narrative is followed by his description of some new reptiles, including the Bahamian green anoles A. fairchildi and A. smaragdinus.

Barbour and Shreve gave these Cay Sal individuals the name fairchildi to honor the individual David Fairchild, the prolific botanist whose name also graces the wonderful Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden (where the recent 7th Anolis Symposium was held!). Let’s pause briefly to consider the man who lends his name to this handsome lizard species. David Fairchild (1869-1954) was a well-known botanical collector, explorer, cultivator, and traveler. Indeed, Pauly (2007) considered him “one of the most important plant explorers in the history of the United States of America.” Like Thomas Barbour of the MCZ, Fairchild was a friend of Allison Armour, and what a great friend for a Caribbean biologist to have. Armour outfitted his 1315-ton steamer Utowana as a research vessel, providing it as a platform for numerous important cruises around the Caribbean and beyond (a “floating palace” according to Fairchild). Wonderful narratives of Barbour (Henderson and Powell 2004) and Fairchild (Francisco-Ortega et al. 2014) aboard the Utowana are definitely worth a read. I particularly love Fig. 2 in the former and consider THAT to have been the good-ol’-days of Caribbean herpetology! As a side note, a name given to Caymanian Anolis conspersus was A. utowanae by Barbour (1932)! You can read more about that interesting story from Steve Poe here or on AA here. Fairchild sailed (well, steamed, really) through the Bahamas at least three times on the Utowana, accumulating a significant amount of botanical knowledge and material. For this reason, and because he was an acquaintance, Barbour named his new anole species after David.

Anolis fairchildi. Photo by Alberto R. Puente-Rolon.

How many people have seen A. fairchildi? Probably not many, and even fewer who appreciated what they were looking at. Cay Sal is a hard place to get to, particularly if one goes via the legal route that necessitates a stopover in Alice Town, Bimini to clear customs (as opposed to running directly, and illegally, from the Florida Keys). Few photos of this species exist, and even fewer narratives of trips in which the species was seen are available.

Anolis fairchildi habitat on Cay Sal Island. Photo by R. Graham Reynolds.

Description

Anolis fairchildi is considered a relatively large green anole, with an SVL of 67–74 mm in males. Barbour and Shreve (1935) suggest it is “allied to” A. smaragdinus and A. porcatus–a natural supposition and borne out in examination–but differing in having “larger dorsal and temporal scales” and also a different coloration. This supposedly diagnostic coloration is a series of white or light blue flecks (comprised of small groups of differently colored scales). James Stroud recently posted a photo of A. carolinensis from Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden that closely resembles the description of A. fairchildi, a humorous and fitting example of the variation present in the former species. A photo of A. fairchildi in Francisco-Ortega et al. (2014) also shows this coloration. Alberto Puente-Rolon and I did not find such distinct spotting in the specimens we examined from Cay Sal Island in 2015. Thus, it seems likely that A. fairchildi does frequently have light spotting, but that this is not a unique phenotype to Cay Sal.

Distribution

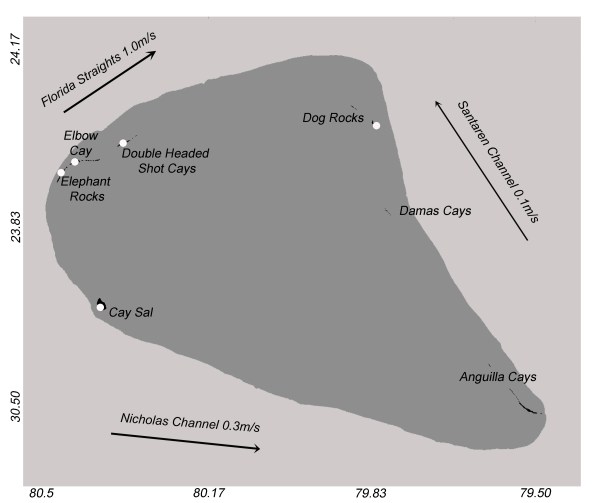

This species is considered endemic to the Cay Sal Bank. Historical records place them on the following islands: Cotton Cay, the eponymous Cay Sal, Elbow Cay, and Double Headed Shot Cays (Buckner et al. 2012). In our cruise to the islands, we did not visit Cotton Cay (=South Anguilla Cay) or North Anguilla Cay, but we did visit the others where the species is thought to occur. We found A. fairchildi on Cay Sal Island only, and observed no individuals on Elbow Cay nor Double-headed Shot Cay.

Map of the Cay Sal Bank, from Reynolds et al. (2018). Note that cotton Cay is part of the Anguilla Cays.

For more, check out our recent publication describing our work on Cay Sal Bank.

A Footnote: how to pronounce this island bank…

Most of us Caribbean ambulators pronounce the word “cay” (=small islands) with a hard k and e sound, like “key.” This apparently is the anglicized version of the Spanish “cayo,” itself possibly cribbed from the Arawak “cairi.” Cay Sal, on the other hand, is frequently pronounced with a hard k and a, as in “cake,” similar to the Spanish. Additional confusion is lent by the historical use of the French word “quay” in the region (originally from the Gaulish “caio”) to refer to docks or gangways present on islands (indeed, small islands would have been dominated by these constructions). An interesting read on all this is González Rodríguez (2016). Any toponomastics buffs have opinions on how Cay Sal should be pronounced?

References

Barbour, T. 1932. On a new Anolis from Western Mexico. Copeia 1932: 11–12.

Barbour, T., and B. Shreve. 1935. Concerning some Bahamian reptiles, with notes on the fauna. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 5: 347–365.

Buckner, S.D., Franz, R. & Reynolds, R.G. 2012. Bahama Islands and Turks & Caicos Islands. In: Powell, R. & Henderson, R.W. (Eds.), Island Lists of West Indian Amphibians and Reptiles. Florida Museum of Natural History Bulletin, 51, pp. 93–110.

Buden, D.W. 1987. Birds of the Cay Sal Bank and Ragged Islands, Bahamas. Florida Scientist 50: 2133.

Francisco-Ortega, J., et al. 2014. Plant hunting expeditions of David Fairchild to the Bahamas. Botanical Review 80: 164-183

González Rodríguez, A. 2016. El Muelle del Cay of Santander City (Spain) and the Two Big European Maritime Traditions in the Late Middle and Modern Ages. A Lexicological Study of the Words Cay and Muelle. 171-178. Names and Their Environment. Proceedings of the 25th International Congress of Onomastic Sciences, Glasgow, 25-29 August 2014. Vol. 1. Keynote Lectures. Toponomastics I. Carole Hough and Daria Izdebska (eds). University of Glasgow.

Henderson, R.W., and R. Powell. 2004. Thomas Barbour and the Utowana voyages (1929–1934) in the West Indies. Bonner zoologische Beitrage 52: 297–309.

Pauly, P. J. 2007. Fruits and plains. The horticultural transformation of America. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- A Victorian Mystery – the Lizard Dewlap - October 10, 2020

- Undergraduates among the Anoles: Anolis scriptus in the Turks & Caicos - July 14, 2020

- Anoles and Drones, a Dispatch from Island Biology 2019 - August 26, 2019

James T. Stroud

This was such a fabulous series of posts! Thanks for writing them up Graham. Jealous of your trip to islands few people have been to and seeing animals that few people have seen!